Bill McMillan ZL2OH was stationed at Quartz Hill. In a personal history that he produced for his family, one of the chapters gives an account of his time at Quartz Hill. This is the interesting story, reproduced here with the kind permission of the author. Also shown are some pictures taken during Bill's time there

QUARTZ HILL

Chapter 9 from the book 'The Delta Ė Reminiscences of a Broadcasting Technicianí by Bill McMillanZL2OH. - There are copies of the book in local public libraries in the Wellington region, also in Auckland, Tauranga, Gisborne, Napier and Christchurch.

********************************

Quartz Hill at 299m is the highest point on a windswept plateau about 8km west-north-west of Wellington City. The Quartz Hill receiving station building is situated just below the summit and some 2km south of Makara Radio, which until finally closed down in 1996, was a receiving station owned and operated by the Post Office. Both radio stations, their associated aerial systems and the staff housing settlement were on land owned by the Government and farmed by the Lands and Survey Department.

Quartz Hill Receiving Station was commissioned by the National Broadcasting Service in November 1944. This followed the initial establishment in 1939 of a small receiving station at Titahi Bay, just across the Paremata inlet and staffed by technicians from the nearby 2YA transmitting station. Its primary function was to pick up the BBC news transmitted on short-wave and rebroadcast on New Zealand national and regional stations that provided the main source of overseas news and information throughout the war years.

Titahi Bay was not a good location for overseas reception, partly because of interference from the 60kW 2YA transmitter. As the Post Office had already established a receiving station at Makara, this was a much better place for a permanent NBS station. The large and relatively flat area north-east of the Quartz Hill summit had ample space for the directional aerials required, and staff accommodation was available nearby. Security was assured by proximity to the Armyís coastal defence gun site guarding the northern approaches to Cook Strait.

Makara Radio provided receiving facilities for international radio communication circuits, and was operated by the Post Office in conjunction with their transmitting station at Himitangi, just north of Foxton. Although the importance of these radio facilities was declining because of the increasing use of undersea cables, Makara Radio in the sixties still had a staff of about 25 technicians and trainees, plus two handymen and a matron who ran the single menís 20-bed hostel.

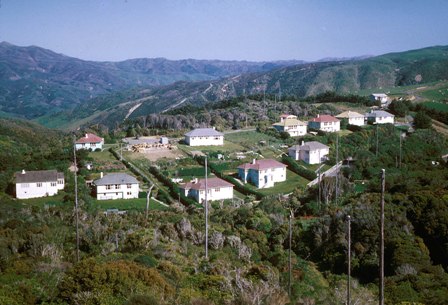

To accommodate all staff who worked at the site, about 20 houses and the hostel had been built in an elevated valley that gave some shelter from the fierce winds of Cook Strait. In addition to the houses occupied by Post Office and Broadcasting staff, a house was provided for the Lands & Survey Department farm manager Bruce Scott, one for his shepherd, and one for Tom Taylor, a technician employed on pasture research by the Department of Agriculture. Four houses for married staff and five beds in the single menís hostel were allocated to Broadcasting, and Quartz Hill staff were expected to live in the accommodation provided. A low rental of only £2 ($4) per week was charged, and for many years a small remote allowance was also paid to staff because of the relative isolation of the settlement. The narrow winding road to Karori was hard on vehicles, especially before the road was sealed in the sixties.

Geoff Andrew, my predecessor, had been at Quartz Hill for 12 years and had moved into the Regional Office as Regional Engineering Officer, essentially as assistant to Regional Engineer Allan Chisholm, and responsible mainly for staffing matters. Quartz Hill operated on a 24/7 basis with a staff of nine technicians. Three basic shifts were worked: 1am to 8.30am, 8.30am to 5pm, and 5pm to 1am, with additional day shifts allowing a midday meal break on weekdays. Technicians who worked at Quartz Hill in the sixties include Michael Lawrence, Neville Newton, George Stewart, Godfrey Gray, Doug MacLean, Russell Lowther, Dene Lynneberg, Selwyn Rodda and Fred Case. There were several others whose names nearly 40 years later I canít recall.

The original station building was used for nearly 15 years. It was replaced in 1958 by a much larger building that contained three control rooms, an equipment service area, a workshop, two offices and a staff room. There was a diesel-powered generator to cover mains power failures, an oil-fired heating system, and a large concrete tank for the water supply.

Two Marconi HR21 independent-sideband HF receivers were the mainstay of the stationís receiving equipment. They were used primarily for maintaining a round-the-clock feed of the BBC World Service to Broadcasting House. Designed for use on international radio-telephone circuits, they were purchased in the early sixties when the advantages of using the sideband reception technique for short-wave broadcasts were finally recognised. These were the ability to select the sideband with the least interference (especially useful in eliminating heterodynes or whistles), and a substantial reduction in the audio distortion caused by selective fading. Each HR21 had separate 6kHz bandpass filters and amplifiers for the upper and lower sideband, and its two audio output channels were fed to faders on the control panel, thus enabling a smooth changeover to the better channel. Each receiver employed about 65 valves (vacuum tubes), and comprised several separate units occupying a complete rack about two metres high. They were relatively difficult to tune and to service, but their shortwave reception quality was superior to that of the nine GEC BRT-402 general-coverage receivers that continued to be used for medium-frequency and less important short-wave reception.

There were also about twelve NZBS-designed fixed-tune receivers for the high-quality reception of New Zealand broadcasting stations, plus a number of other specialist receivers for various purposes. One of these was an Eddystone 680X receiver mounted on the main control room desk and fitted with a calibrated external signal strength meter. This was an all-purpose receiver in constant use by the duty operator for search and monitoring purposes. Each control room was equipped with a ten-channel mixing console, two tape recorders and miscellaneous aerial switching and other control facilities. There were six programme landlines to Broadcasting House.

The directional aerial system was quite elaborate. Two main types of aerial were used, rhombics and vees. Any one of the four rhombic aerials could be switched to provide reception of European stations (usually the BBC) on either the long-path (south-east) or short-path (north-west). They were each supported by four 21-metre hardwood poles, each leg comprising three spaced wires about 100 metres long. Thirteen terminated vee aerials with an average leg length of 250 metres were available for reception from stations around the world, and also for the reception of New Zealand broadcast stations.

For reception of European, North American and Australian stations, two similar aerials spaced several hundred metres apart were provided to enable diversity reception, an early technique to reduce the effects of signal fading. It required two or more receivers with separated aerials to be connected to a common output, and was seldom used after the HR21 receivers were commissioned. The vee aerials were not as effective as the rhombics, but they had the advantage of requiring only one 21-metre pole, and several aerials could be suspended from the same pole. All the aerials were connected by 4-wire feeders to matching transformers mounted on gantries near the station, and then via buried coaxial cables to a termination room. In normal use, each aerial could be connected to a multi-coupling device to allow several receivers to be fed from the same aerial. There was also a dipole aerial for general reception, supplemented later by two long-wire Beverage aerials for receiving weak MF stations. The Eddystone 680X search receiver was fed by a 6m whip aerial mounted on a pole adjacent to the main control room. This aerial received such a battering from frequent gales that it usually had to be replaced every few months.

Operational procedures were well established. As well as maintaining a feed of the BBC World Service to Broadcasting House, Quartz Hill provided reception, mainly for Wellington news and sports personnel, of overseas and domestic programmes (often sports-related) from various sources such as Radio Australia, the Voice of America, and medium-frequency stations elsewhere in New Zealand when wide-band programme lines were not available.

All BBC short-wave transmissions were monitored hourly, and reception reports airmailed weekly, as were SIO reception reports (signal strength, interference and overall merit on a 1 to 5 scale) on transmissions directed to New Zealand by ten other countries. Ten-minute BBC news bulletins were still being rebroadcast several times a day by 2YA and other national and regional stations, and all bulletins were recorded on tape. Tapes were re-used in strict sequence, so that it was possible to refer back to any bulletin recorded in the previous ten days or so. Recordings of earlier bulletins were used when reception of the BBC was unsatisfactory at the time, often the case at 6am.

Other activities included regular monitoring of the short-wave bands for the International Frequency Registration Board (IFRB) in Geneva. The information gained was also used to assist in preparing operational schedules for the short-wave service of Radio New Zealand. These schedules were prepared at Quartz Hill four times a year and six months in advance for the IFRB, which was represented in New Zealand by the Post Office. A good deal of administration was involved, generating large quantities of paper, most of it quite useless. In 1968 the purchase of a Racal RA17 receiver and a frequency counter enabled us to take over from the Post Office the monthly frequency measurement of all Radio New Zealand stations to ensure that they were within tolerance.

It didnít take me long to get into an enjoyable routine in the job. I revised the operational procedures to bring them up to date, and I convinced the technicians that it was not essential to realign receivers every six months. My experience was that unnecessary maintenance often caused rather than prevented equipment performance problems (if it ainít broke, donít fix it!). On Thursday afternoons I took the station van (used at each change of shift for staff transport between the station and the settlement) to visit the Regional Office in Broadcasting House. I got on quite well with the Regional Engineer Allan Chisholm, although our working relationship was rather more formal than necessary. This visit seldom took more than an hour or so, and there was usually plenty of time to do any other business before returning to Quartz Hill before the shift change at 5pm.

In October 1966 I was required to attend a three-day course in Public Administration at Victoria University. There were 40 others on the course, many from City Councils in the Wellington area. I didnít get much from the course; role-playing games were not really my scene. However it was a useful insight into the thought processes of people responsible for making the political system work.

Our community amenities were well organised. A full-sized billiard table in the hostel, a tennis court and a childrenís play area were available for all residents. The Karori milkman delivered milk to a box at the foot of the access road; this was picked up by the Post Office handyman every weekday morning and delivered to the residents. On weekends and public holidays, residents took monthly turns to pick up the milk and deliver it. Mr Robb, who owned the Four-Square store at Makara village, delivered bread and groceries three times a week. Meat could be ordered from any butcher in Karori and picked up by the Post Office handyman on Mondays and Thursdays. Mail was delivered to the hostel each weekday except Tuesday, and the ĎEvening Postí newspaper every night at about 5pm. The Post Office handyman collected rubbish every Monday morning.

We were all expected to take turns on the Social Club committee. This involved organising farewell parties held in the social room at the hostel for Post Office and Broadcasting staff being transferred elsewhere. The more formal part of the evening ended after a large supper and a suitable presentation to the person or family leaving. If it was one of my staff, I had to make a farewell speech; a job I disliked Ė public speaking was never one of my strong points. Considerable quantities of alcohol were consumed, but I donít recall any serious incidents on the access road caused by over-the-limit drivers, and sale of the empties boosted the School Committee funds.

One of the annual events organised by the committee was a community Guy Fawkes bonfire combined with a sausage sizzle. This was held on level ground at the site of the wartime army camp near the gun emplacements. An exciting night for the children, there was the usual element of danger associated with fireworks, but we were lucky that no serious incident occurred during our three years at Makara.

Life in a remote settlement was a lot different from what we expected when I first decided to apply for a job in Wellington, and it took a little while for Joan and the children to settle in. So far as I was concerned, this was the most enjoyable job I ever had. Any problems that cropped up (usually some minor misunderstanding) were easily sorted out by a chat with my opposite number in charge of the Post Office station. He had three times the number of people on his staff, and there was considerable rivalry between Broadcasting and Post Office staff, with a regrettable tendency for the former to consider they were a Ďcut aboveí the latter (the reverse was possibly also true). However, as Broadcasting leased its facilities from the Post Office, we were the junior partners, and I had no difficulty accepting this situation.

Sue was eleven when we moved to Makara, and not at all happy about leaving Tauranga and her friends Sheryl Isaac, Patty Seales and Cynthia Draper. However, some months later the Post Office appointed Bruce (ĎTinnyí) Hogan to take over from Rex Beechey as Superintendent, and Sue began a lasting friendship with Bruceís daughter Lorraine. Several years later, Bruce became the first Superintendent of the new satellite station built by the Post Office at Warkworth.

At first, Sue and John attended the Makara Model School. They went on the school bus that came up to the settlement for the primary school children after taking college children to the Karori bus terminus. The latter were required to catch the bus at the foot of the access road. Residents took turns to take them down the hill at 7am and pick them up again at 5pm. It was a long day, especially for the children who had to travel by bus across the city to colleges near the Basin Reserve.

As parents, we often met Brian Barrett, the head teacher at the Makara Model School, and I soon became involved in the School Committee as Secretary-Treasurer. This kept me busy. As well as having to attend a monthly meeting, which usually generated correspondence to be actioned, my weekends were occasionally taken up by fund-raising activities such as bottle drives. There were always plenty of bottles.

Merv Buxton, one of the teachers at the school, was a keen bowler, and he persuaded me to join the Terawhiti Bowling Club near the bus terminus in Karori Road. This was a great game, and I enjoyed playing on most Saturday afternoons during the late spring and summer. After we moved to Tawa, I joined the Tawa Services Club, but I eventually gave up bowling because it was taking too much of my weekend time, partly due to the element of compulsion inherent in playing a team game involving organised competitions, sometimes at other clubs.

Joan joined the Makara badminton club and played in the village hall. She also joined the tennis club, which used the court at Makara School. We also played an occasional game of tennis on the court at the station. The rest of our spare time was often taken up by weekend visits to Joanís family at Raumati. We usually took the short cut on the narrow unsealed road through the Takarau Gorge to Johnsonville.

In 1968 we decided to try a caravan holiday. We hired a medium-sized van at Easter and headed north, first to New Plymouth where the rain never stopped. We stayed for two nights before carrying on northwards to spend several days in the Domain camp at Mount Maunganui. It was a learning experience, but apart from the negative reaction of Sue and John to the rather garish orange and brown caravan, we had a successful trip. In January 1969 we decided to buy a new 14-ft caravan, a Liteweight Vagabond for which we paid about $1500. For the next decade we used this for our summer holidays, mostly at one of the caravan parks at Mt Maunganui, where we were often joined by our friends Pam and Don Ward. Our longest trip was in the early seventies to Taipa, a beach resort east of Kaitaia. In later years, parked on the back lawn at Hillary Street with its wheels off, our caravan continued to serve us well as a sleepout and for storage.

The most memorable event that occurred during our time at Makara was the great Wahine storm. On Wednesday morning 10 April 1968 we awoke to a strong southerly gale. As this was not unusual, we all began with our normal routines. Schools were open, buses were running, and Sue, John and Helen went off to school as usual. At 8.30am I drove up in the van with the day shift staff to the station. We were buffeted by the wind on the exposed access road, but this did not seem to be very much worse than during some previous storms. It was not until later in the morning that we heard that the ferry Wahine was in difficulties after striking Barrett Reef while trying to enter Wellington harbour on its overnight trip from Lyttleton. With more reports of damage coming in, it was obvious that the storm was much more severe than usual. We did not realise just how bad it really was until we heard the dramatic reports on the plight of the Wahine, which after being driven by the storm through the harbour entrance, finally rolled over and sank near Seatoun with the loss of 57 lives.

Because of the worsening weather, Makara School decided to send their primer class home at about midday. Helen was in this group. The school bus was unable to get all the way up to the settlement because pine trees were being blown down across the access road at the first cattle stop. It was indeed fortunate that Helen and the other children managed to get past this dangerous area without injury. Sue and John came home later, after the worst of the storm had passed. Our house escaped serious damage, but a row of tiles on the southern side of the roof was blown off, resulting in pools of water accumulating in the ceiling of our bedroom. If the storm had continued for much longer, we would have lost the whole roof. Up at Quartz Hill, most of the aerials survived undamaged. We were lucky to escape so lightly. The strongest wind gust reported in the storm (145 knots or 268km/h) was recorded at Oteranga Bay, a few kilometres south of Quartz Hill, before the anemometer there was put out of action by the hurricane-force winds.

Oteranga Bay is where the NZ Electricity Department established the northern terminal of their 600kV DC power cable across Cook Strait. I was once taken to visit this facility by an NZED engineer. The access road branches off the South Makara road, starting with a steep climb of some 300m westwards up on to a ridge, then south-westwards for several kilometres before descending to the terminal. Here at the time a resident caretaker spent a lonely life. A short-lived gold rush took place in the Terawhiti area in the 1860s, and we stopped off near Mt Misery on the way back to have a close look at one of the old mining tunnels, some of which are still visible from the access road. They are not much more than a metre in diameter and hardly changed in well over a century.

The NZED originally planned to route their 600kV DC power lines between Oteranga Bay and Haywards quite close to the Quartz Hill aerial system. However, the radio noise generated by the DC/AC converters at Haywards and radiated by these lines would have affected the reception of weak signals at both Quartz Hill and the Makara Receiving Station. Strong protests from the NZBS and the NZPO resulted in the power lines being built about a kilometre east of the original route. Years later in 1992, following concerns about adverse health effects from strong electric fields, another section of the same power line was relocated north of its original route across the Churton Park housing area near Johnsonville.

It was an easy walk down to Te Ikaamaru Bay, one of the more remote spots in the area, and on one occasion we walked further on over the rabbit-infested ridge to Ohau Bay and then up the valley to Black Gully where some of the old cast-iron machinery used during the gold mining years lay rusting on the ground. A small bach near the beach at Te Ikaamaru Bay was owned by Ted Hall, who had a small repair business in the Kelburn shopping area. He often called in at the station on Friday evenings for the key to the access track. It was a peaceful and remote place for a weekend bach, and although only half an hour or so from the city, its existence would have been known to very few.

As a footnote, in 2005 in the face of fierce opposition from Makara residents living along the valley, resource consent was granted for Meridian Energy to construct a 70-turbine wind farm covering 56 sq km on Makara Farm and Terawhiti Station that will produce 210MW. Following appeals by several parties, in 2007 the Environment Court reduced the number of turbines to 66. The station building at Quartz Hill, leased from Meridian Energy by a group of Wellington radio amateurs who took it over when Radio New Zealand vacated the site, will be used as a control base for Project West Wind. ZL6QH uses some of the original aerials for some outstanding results, but it is not yet certain whether the amateurs can continue to operate on the site due to the possibility of interference from the generators.

After three years my job at Quartz Hill was not much of a challenge. Not only was the importance of shortwave reception declining because of continuing advances in communications technology, but my family was being disadvantaged by the poor road to the city that made it difficult for older children to participate fully in sporting and other activities. It was obvious too that living in rented housing in an isolated community was not in our best long-term interests. Change was again on the cards.

During the sixties, radio had given way to television in the allocation of resources, and by 1969 the majority of the Corporationís engineering staff were involved in extensions to television coverage and the establishment of a microwave programme link between the four main cities that would enable the same programme to be transmitted by all stations. Additional staff were continually being sought for this work, so when Andy Chirnside, team leader of the Communications Section of the Microwave Group, was appointed to the position of Regional Engineering Officer in Christchurch, I agreed to be seconded to Head Office from 23 June 1969 to carry on the work he had been doing. I applied for the vacancy, and on 30 July I was formally appointed to the position of Technical Officer, Class A, Head Office, Grade 10 on a salary of $4090 per annum.

Makara Radio houses looking east

Joan on hill above Opau Bay, Makara

Joan on hill above NZPO Makara Radio Station

Looking north to Kapiti Island from Makara hills

![18 Makara H4 [ours] & H5 [Taylors] looking east.jpg](http://www.ZL6QH.com/logs/18 Makara H4 [ours] & H5 [Taylors] looking east.jpg)

Makara H4 [ours] & H5 [Taylors] looking east

Entrance to Makara Radio village looking south

Quartz Hill receiving station c1967

Makara Radio village looking SE